Before the Stadiums, There Was a Voice

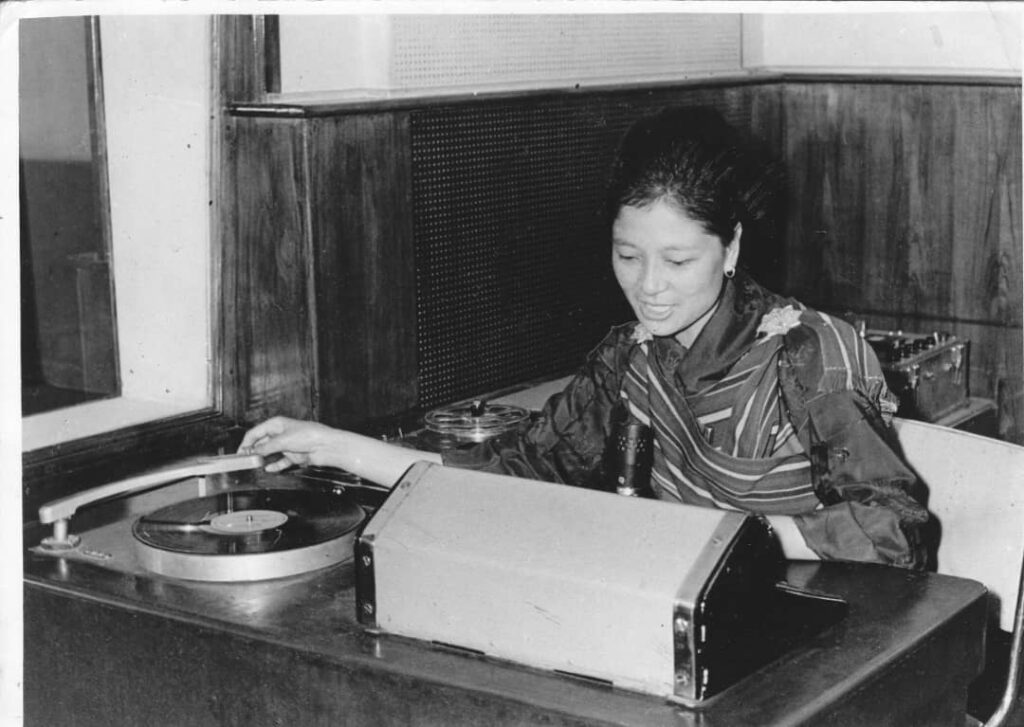

A Tribute to Yeshi Peldon, The First Dzongkha Radio Jockey

By Victor Gurung, Media and Technical Lead Consultant, Bhutan Olympic Committee

Sometimes, stories don’t come wrapped in medals or headlines. They come in the calm voice of an 85-year-old woman who greets you with warmth, a sense of quiet pride, and memories that echo through the hills and valleys of our past. This is a story I carry with reverence—one that found me in Thimphu and left me with a profound sense of humility. It is the story of Aum Yeshi Peldon—the first woman from Bhutan to become a Dzongkha Radio Jockey for All India Radio, Kurseong

Aum Yeshi is the voice of a time when dreams had to cross rivers on foot, when education wasn’t a birthright but a burning desire, and when the airwaves were the only bridge between the people and the world beyond the mountains.

Born in 1941 in Punakha, Yeshi Peldon was the youngest of nine siblings. There were no roads, no schools—just wide valleys, simple lives, and a child’s stubborn wish to study. Until she was five and a half, she learned from her family at home. From there, she moved to a lhakhang (monastery), where she was immersed in scriptures, prayers, and Dzongkha-Tibetan script. That was all there was, and she absorbed it like sunshine on a mountain morning.

In 1960, during a pilgrimage to Sikkim with her mother, her life took an unexpected turn. After the festival, they visited Kalimpong, and something clicked. Amid the bustle and whispers of a changing world, Yeshi saw the open doors of education and said, “I want this. I want to study.”

She found a kind-hearted Buddhist teacher who saw the light in her eyes. For two years, he taught her Tibetan, English, and nurtured her thirst to speak, to write, and to dream out loud. At 19, with no formal school certificate in hand, she had something far more powerful: courage, curiosity, and voice.

In 1962, the newly launched All India Radio station in Kurseong was looking for someone to read Dzongkha news—someone who could connect Bhutanese communities with essential updates on health, agriculture, women’s rights, and development. There was no media center in Bhutan then, no studio, no blueprint—just a transmitter and an idea.

Yeshi was selected. Just like that, a woman who once prayed in lhakhangs became the first voice of Bhutan on All India Radio station in Kurseong, beginning with a monthly salary of Rs. 200.

“I used to laugh,” she told me, “because rice cost 50 paise per kg back then. Life was simple, but this job—it meant everything.”

Her early work included reading Kuensel news—a paper she still doesn’t know how it reached Kurseong—and scripting it in her own hand. And yes, she read sports news too.

But sports then were different. They weren’t played in stadiums; they were played on open fields, in courtyards, between communities. Dha (traditional archery), Dhego (stone throwing), Sosum (a game of skill and aim), and Jedum (a form of discus throw) were not just games—they were part of life. Men would come together in their ghos, each representing their village with pride. Victories were celebrated with local feasts, and losses accepted with cheerful laughter. These games built identity, community spirit, and even diplomacy between gewogs.

Yeshi’s voice brought these events to life. “There was no camera. No photograph. Just my voice,” she said. “I used to read the names of the winning villages, and the scores. People would listen with excitement, especially if their relatives were playing.”

There were no mentions of football or volleyball—because they simply didn’t exist in the community’s vocabulary then. Sports as we know them today had not yet arrived in Bhutan. But what did exist was a deep-rooted love for physical challenge, friendly competition, and local pride.

And through Yeshi’s broadcasts, even the smallest village tournament gained recognition. Her sports updates didn’t just inform—they honored. A team from a remote valley hitting the bullseye in Dha got the same airtime as a government announcement. That, in its own way, was national unity.

I could feel the weight of her stories. She wasn’t just reporting news; she was weaving connection—between villages, between Bhutan and the world, between generations.

One of the most moving moments she shared with me was this: “We needed a permit to own a radio. Only a few families had one. But during my broadcast, when a Dzongkha song would play, the whole village—the entire village—would dance together around one radio. Just one radio. That sound, that joy—it’s something I will never forget.”

I could see her eyes sparkle as she spoke, reliving that harvest day in Punakha when she saw her community singing along to her voice, echoing from a little box in someone’s home. How powerful a moment must that have been for a young woman who once begged to study?

She laughed, “Even now, sometimes I wish to speak just once more on the radio. That feeling—it never leaves.”

Aum Yeshi served as a radio jockey for 35 years, from 1962 until her voluntary retirement in 1995 at the age of 54. But her voice went far beyond the airwaves.

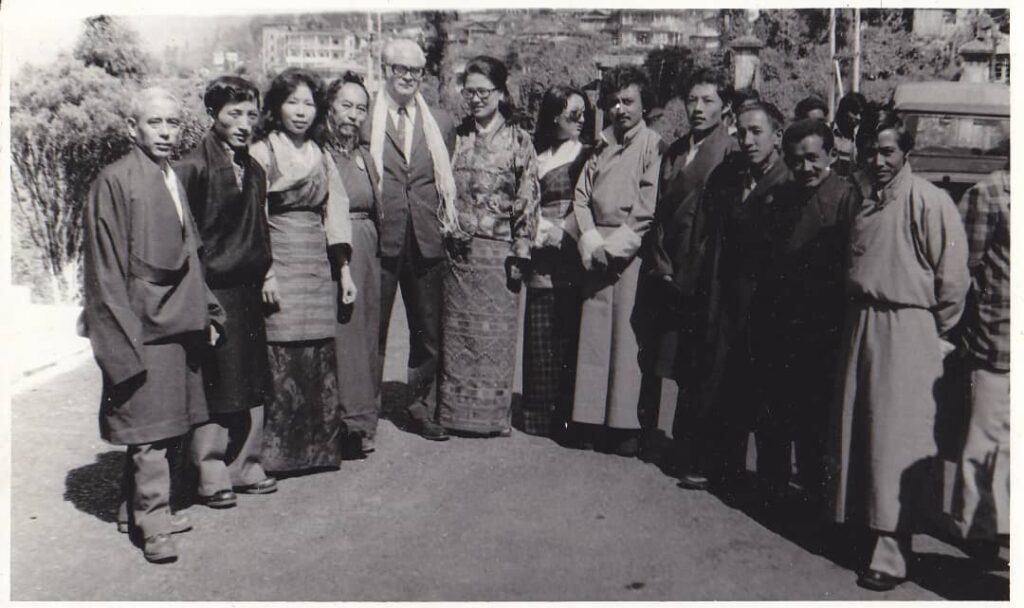

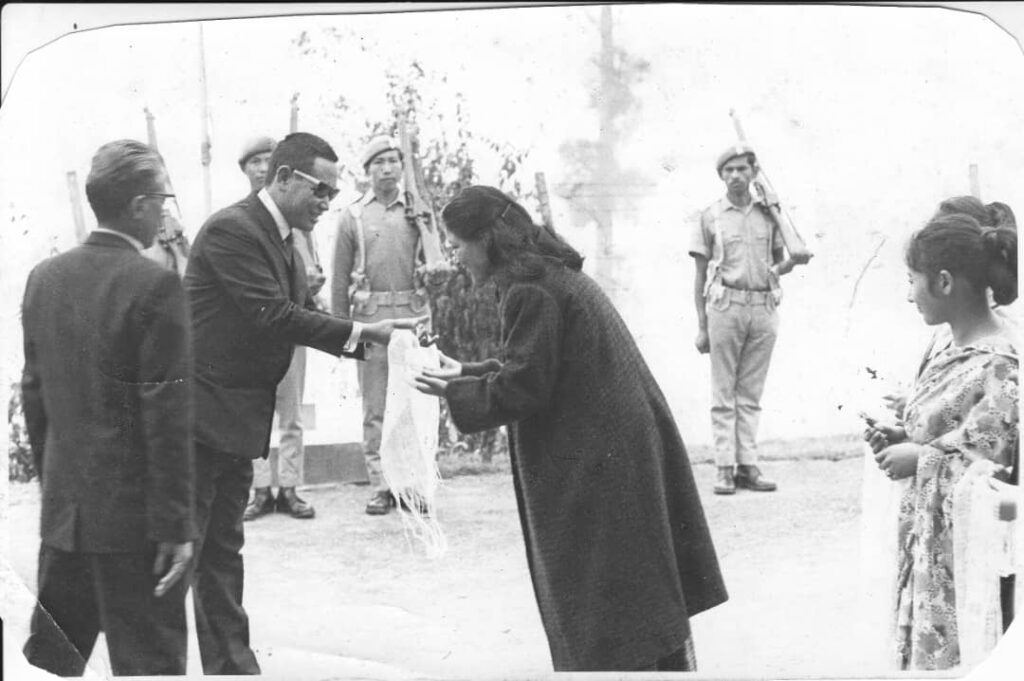

She met Jawaharlal Nehru, then Prime Minister of India, and his daughter Indira Gandhi, who was then the Information Minister. She danced before His Majesty Jigme Dorji Wangchuck, Bhutan’s Third King, and still remembers the gentle tap on her shoulder and his words: “Aum Yeshey, good work.”

She even had the rare opportunity to interview His Holiness the Dalai Lama—a memory she holds like a sacred prayer.

As someone deeply involved in Bhutan’s Olympic movement, her story touched me in a very personal way. She told me how sports transformed over the years—from simple village games to televised competitions, from Dha to football.

“I didn’t know about football in my time,” she said with a chuckle, “but now I see Bhutanese boys and girls on TV, playing, winning, wearing our flag on their chest—it makes me proud.”

She reminded me of a time when radio was the only bridge, when people listened with hearts wide open, when a woman’s voice reading about archery was a revolution in itself.

As someone deeply involved in Bhutan’s Olympic movement, her story touched me in a very personal way. She told me how sports transformed over the years—from simple village games to televised competitions, from Dha to football.

“I didn’t know about football in my time,” she said with a chuckle, “but now I see Bhutanese boys and girls on TV, playing, winning, wearing our flag on their chest—it makes me proud.”

She reminded me of a time when radio was the only bridge, when people listened with hearts wide open, when a woman’s voice reading about archery was a revolution in itself.

Before I left, she placed her hand on mine and said:

“You all are lucky. You have everything—schools, teachers, cameras, TV, stadiums. Don’t waste your time. Be grateful. Be responsible. Don’t use technology to hurt others. Use it to uplift your country. Work with integrity. Do your part. Bhutan needs you all.”

I walked away that day carrying more than a story. I carried her legacy.

So when we speak of sports in Bhutan, let us not forget the woman who once read about a village’s archery match, and in doing so, made them feel like champions.

Let us not forget that before there were medals, there were voices.

And one of those voices belonged to Yeshi Peldon.

Latest Updates and Insights

Discover our newest blogs, news, and announcements—curated just for you. Stay informed and inspired!

THE WORLDWIDE OLYMPIC PARTNERS